Bibliography

Aguirre, P. ‘Writing on the Wall: Interview with Experimental Jetset’ (2022) [online] Available at https://www.academia.edu/73248498/Writingonthewall_Jet_Set_Peio_Aguirre_ENG [Accessed 22 March 2025].

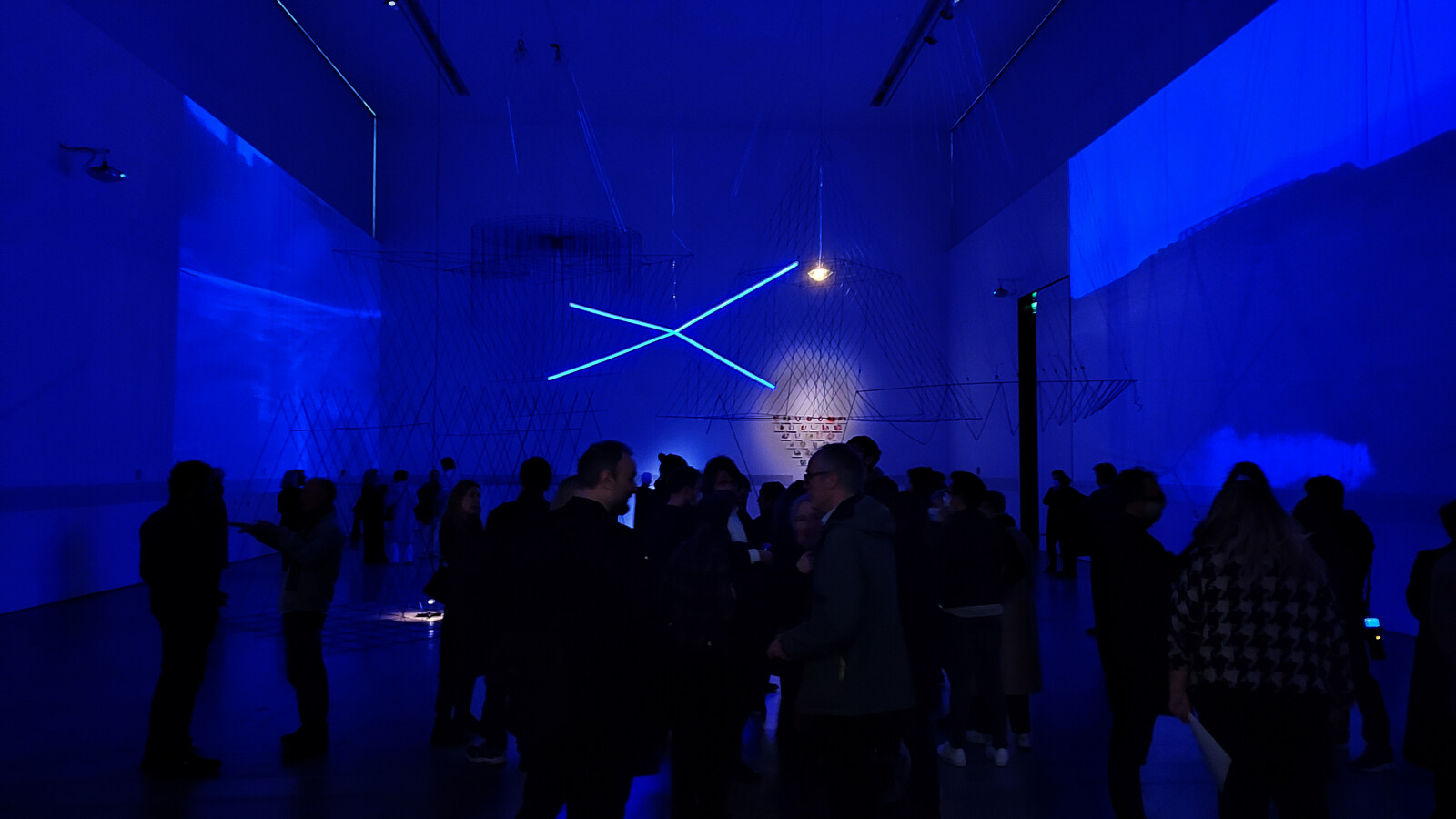

Anderson, S. (2018) ‘Notes on Signals, Spectres and Systems’. A Late Evening in the Future: Signal, Spectre, System, 39–46 Vienna: VfmK Verlag für moderne Kunst GmbH.

Bailey, P. (2018) A Line Which Forms a Volume. Stuart, M. & Bailey, P. (eds.). London: London College of Communication.

Barthes, R. and Heath, S. (1978) Image, Music, Text. New York: Hill and Wang.

Benjamin, W. (1999) The Arcades Project. Massachusetts, London: Belknap Press.

Benjamin, W. (2008) ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. London: Penguin.

Blauvelt, A. (2003) ‘Towards Critical Autonomy or Can Graphic Design Save ITSELF?’ Emigre: Rant 64, 38–43. California: Emigre/ New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Blauvelt (2013) The 2013 D-Crit Conference: A. ‘Graphic Design: Discipline, Medium, Practice, Tool, or Other?’ [online] Available at: https://vimeo.com/showcase/2359892/video/66385792 [Accessed 22 March 2025].

Bloom-Christen, A. and Grunow, H. (2022) What’s (in) a Vignette? History, Functions, and Development of an Elusive Ethnographic Sub-genre, Ethnos. [online] DOI: 10.1080/00141844.2022.2052927 Available at https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2022.2052927 [Accessed 22 March 2025].

Bolter, J.D. and Grusin, R.A. (1999) Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Borsuk, A. (2018) The Book. Massachusetts: The MIT Press, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Bourriaud, N (2002). Relational Aesthetics. Dijon: Les Presses du Réel.

Bringhurst, R. (2004) The Solid Form of Language: An Essay on Writing and Meaning. Kentville: Gaspereau Press.

Buzon, D. ‘Design Thinking is a Rebrand for White Supremacy: How the Current State of Design is Simply a Digitally Updated Status Quo’ [online] Available at: https://dabuzon.medium.com/design-thinking-is-a-rebrand-for-white-supremacy-b3d31aa55831 [Accessed 22 March 2025.

Carswell, S. (2012) Anglo Republic: The Definitive History of the Bank That Brought Ireland to Ruin. London: Penguin.

Chion, M. (2017) Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen. New York: Columbia University Press.

Clarke, J. (2003) ‘Style: The Creation of Style’, Resistance Through Rituals Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain, 175–191. Hall, S. and Jefferson, T. (eds.). London and New York: Routledge.

Davis, E. (2002) ‘Recording Angels: The esoteric origins of the phonograph’, Undercurrents: The Hidden Wiring of Modern Music. London: Bloomsbury.

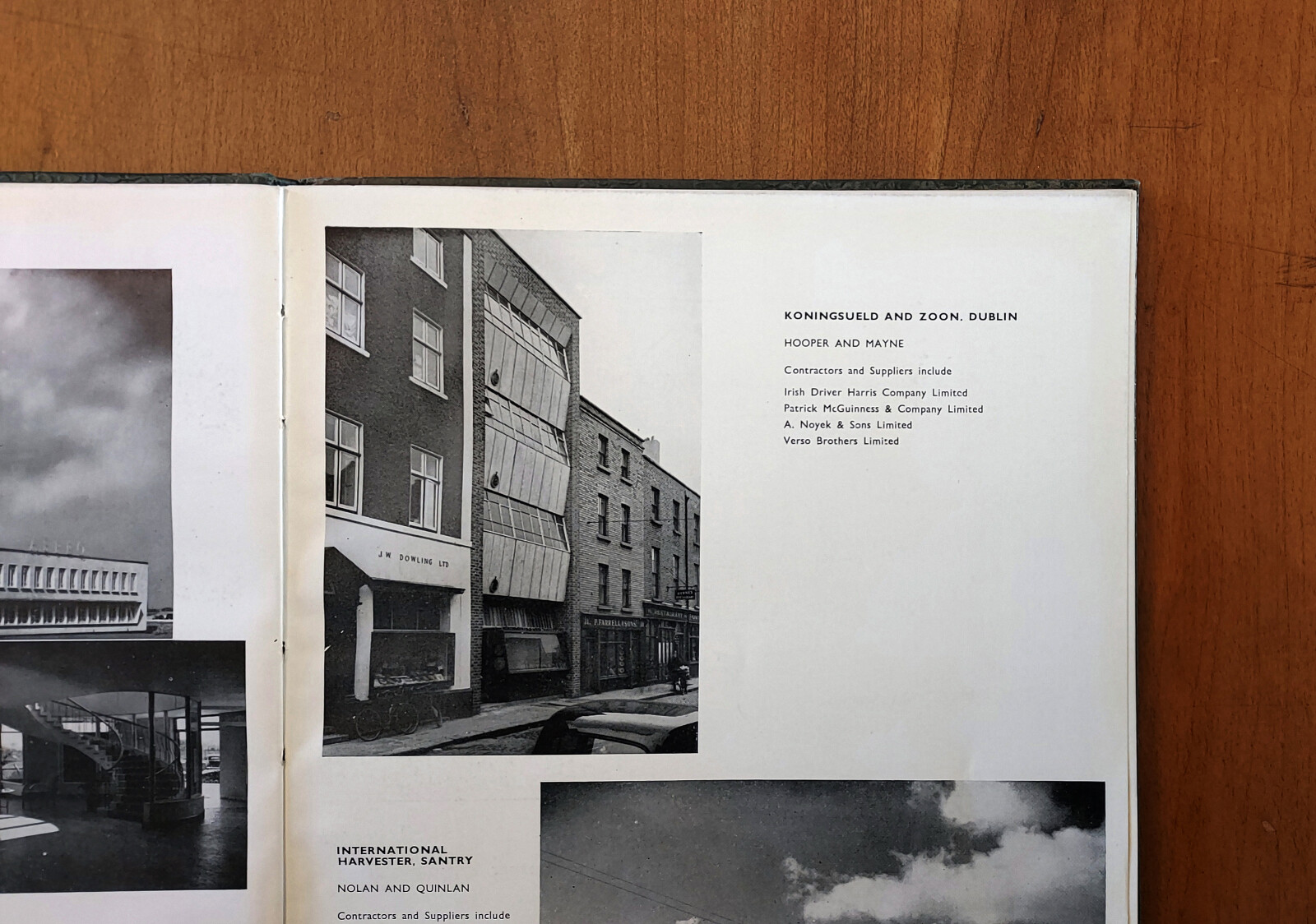

dePaor, T and Maybury, P. (2013), ‘Inter Alia’, San Rocco – What’s Wrong with the Primitive Hut? 8, 142–5. Milan: San Rocco.

de Certeau, M. (1988) The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

Denisoff, R.S., and Peterson, R.A. (1972) Sounds of Social Change. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Denzin, K. & Lincoln, Y. (2013) The Landscape of Qualitative Research. London: Sage.

Derrida, J. (1978) ‘Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences’, Writing & Difference. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; and London: Henley, Routledge and Keegan Paul Ltd.

Drucker, J. (2014) Graphesis: Visual Forms of Knowledge Production. Cambridge, Massachusets; London, Harvard University Press.

Duchamp, M. (1999) À l’infinitif. Hamilton, R. and Bonk, E. (eds.). The Typosophic Society: Northend Chapter.

Duncombe, S. (1997) Notes from the Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture. Bloomington, In: Microcosm.

Eco, U. (1989) The Open Work. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press.

Fiske, J. (2011) Television Culture. Oxford and New York: Routledge.

FitzGerald, K. (1997) ‘Fuel Full Pull Poll Pool Cool Cook Book’, Emigre: Design as Content 44, 14–28. California: Emigre.

FitzGerald, K. (2010) Volume: Writings on Graphic Design, Music, Art, and Culture. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Forde, G. (1991) ‘The Designer Unmasked’, Eye 23, 57–68. London: Eye Magazine Limited.

Friedman, S. (1991) ‘Weavings: Intertextuality and the (Re)Birth of the Author’, Influence and Intertextuality in Literary History, 146–180. Clayton and Rothstein (eds.). Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press.

Foucault, M. (1979) ‘What is an Author?’, Textual Strategies 141–160, Josué Harari (ed). Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Foucault, M. (2020) ‘What is an Author?’, Aesthetics: Essential Works 1954–84. UK: Penguin.

Genette, G. (1997) Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press.

Gilloch, G. (2002) Walter Benjamin: Critical Constellations. Cambridge: Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Goggin, J. (2012) ‘2009: Practice from Everyday Life: Defining Graphic Design’s Expansive Scope by Its Quotidian Activities’, Graphic Design: Now in Production, 54–56. Blauvelt, A. and Lupton, E. (eds.). Minneapolis: Walker Art Center.

Goodwin, A. (1992) ‘Rationalisation and Democratization’, Popular Music and Communication. Lull, J. (ed). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Grumet, M. (1987) ‘The Politics of Personal Knowledge’, Curriculum Inquiry, Autumn, 1987, 17, (3), 319-329. Blackwell Publishing on behalf of the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education/University of Toronto.

Hall, S. (1979) ‘Culture, the Media and the “Ideological Effect”’, 315–348, Mass Communication and Society. Curran, J. et al (eds). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hart, J. (1980) Preface to On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects. University of Western Ontario.

Hebdige, D. (2010) Subculture: The Meaning of Style. London and New York: Routledge.

Heller, S. (1996) ‘The Man who Invented Graphic Design’, Eye 23. London: Eye Magazine Limited.

Heller, S. (2018), ‘Octavo: Eight Historic Issues’ Print. [online] Available at: https://www.printmag.com/daily-heller/octavo-eight-historic-issues-unit-editions/ [ Accessed 22 March 2025].

Hutchinson, J. (1997) The Bread and Butter Stone: On Memory. Dublin: The Douglas Hyde Gallery.

Hutchinson, J. (ed.) (1999) Utopias. Dublin: The Douglas Hyde Gallery.

Hutchinson, J. (2005) Huts. Dublin: The Douglas Hyde Gallery.

Jackson, M. (2017) ‘After the Fact: The Question of Fidelity in Ethnographic Writing’, Crumpled Paper Boat: Experiments in Ethnographic Writing. Pandian, A. and McLean, S. (eds.). Durham: Duke University Press.

Jensen, K. B. (2016) ‘Intermediality’, The International Encyclopedia of Communication Theory and Philosophy. Jensen, K. B. and Craig, R.T. (eds). Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley & Sons.

Johnson, B. (1987), ‘Les fleurs du Mai Arme. Some Reflexions on Intertextuality,’ A World of Difference. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

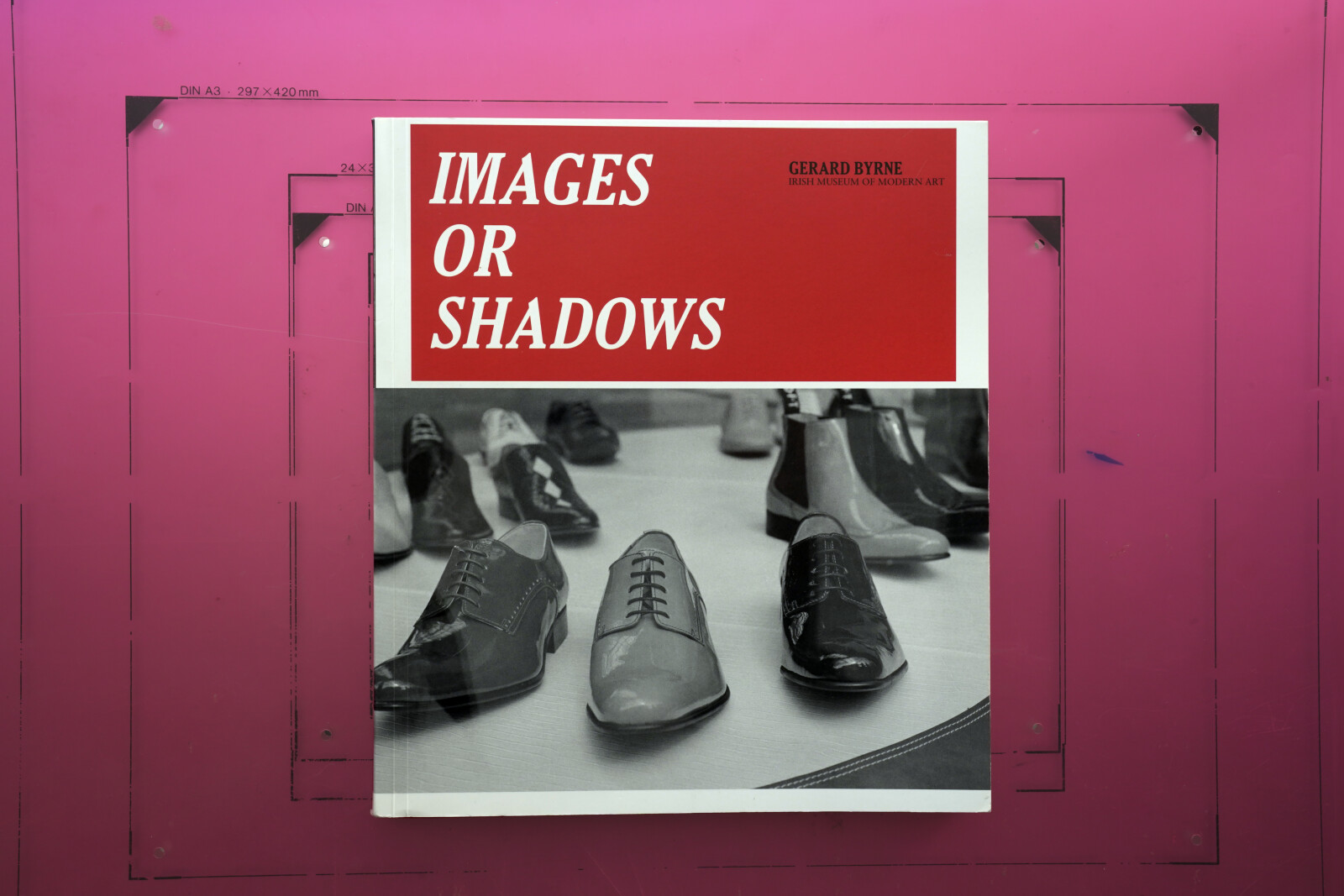

Juncosa, E. (2011) ‘On the Subject of the Existence of Monsters’, Images or Shadows, 135–142. Dublin: Irish Museum of Modern Art.

Jones, T. (ed). (1990–91) i-D 80, 38–51; 89, 22–25; 93, 38–43.

Kim, K. (2022) The Thin Air, 2, 29. Coney, B. et. al. (eds.)

Kincheloe, J. (2005) ‘Continuing the Bricolage’ Qualitative Inquiry, 11 (3); 323–50. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Kittler, F. A. (1999) Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Koonts, L. (1995) ‘Table Coffee Talk’, Emigre 36: Mouthpiece, n. pag. California: Emigre.

Kristeva, J. (1980) Desire in Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art. New York: Columbia University Press.

Lafuente, P. (2011) ‘Texts, Paratexts, Hypertexts’, Images or Shadows, 3. Dublin: Irish Museum of Modern Art.

Leroi-Gourhan, A. (1993), Gesture and Speech. Cambridge/ London: The MIT Press.

Liestman, D. (1992) ‘Chance in the Midst of Design: Approaches to Library Research Serendipity’, RQ, Summer 1992 3 (4), 524–32 American Library Association.

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1966) The Savage Mind. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Louridas, P. (1999) ‘Design as Bricolage: Anthropology Meets Design Thinking’, Design Studies 20 (6). [online] Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0142694X98000441 [Accessed 22 March 2025].

Lull, J. (1992) ‘Popular Music and Communication: An Introduction’, Popular Music and Communication. Lull, J. (ed). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Lupton, E. (1991) ‘The Academy of Deconstructed Design’ Eye 3 (1). London: Eye Magazine Limited. [online] Available at: https://www.eyemagazine.com/feature/article/the-academy-of-deconstructed-design [Accessed 28 March 2025].

Lupton, E. (2012) ‘The Designer as Producer’, Graphic Design: Now in Production. Minneapolis: Walker Arts Centre.

Lupton, E. & Blauvelt, A., (eds.) (2012) Graphic Design: Now in Production. Minneapolis: Walker Arts Centre.

Maybury, P. (1997) The White Book. Self-published.

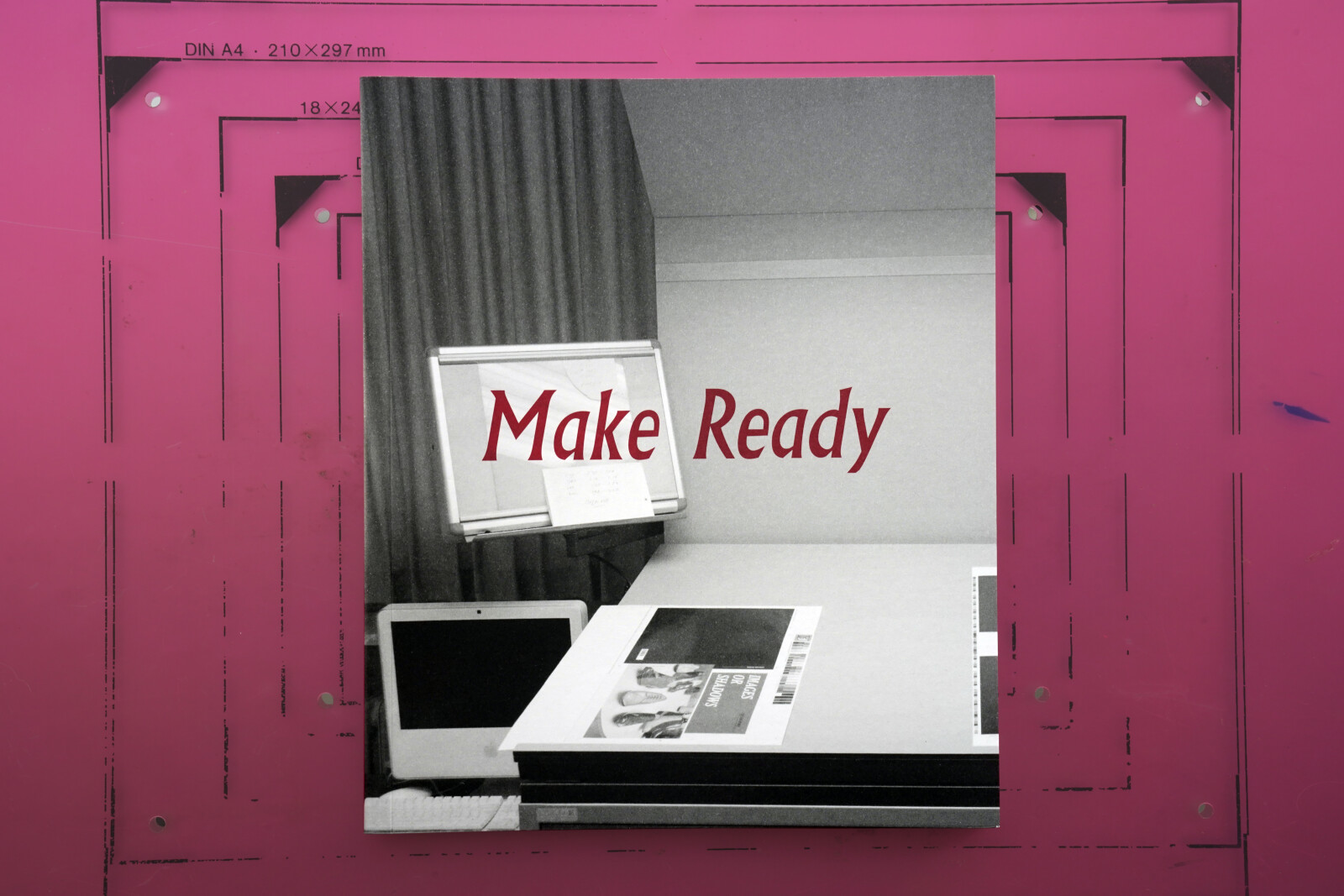

Maybury, P. (2015) Make Ready. dePaor, T., McNulty, D. (eds). Dublin: Gall Editions/Ways& Means.

Maybury, P. (2015b) ‘Peter Maybury’, Ways&Means, n. pag. Dublin: Ways&Means.

Maybury, P. (2022a) ‘Your Sound Position’, W/HERE: Donohoe, D., n. pag. Available at: https://daviddonohoe.bandcamp.com/album/w-here [Accessed 22 March 2025].

Maybury, P. (2022b) ‘Throw Away’, Throw Away. Maybury, P. & Nugent, C. (eds.). Dublin: Image Text Sound Editions.

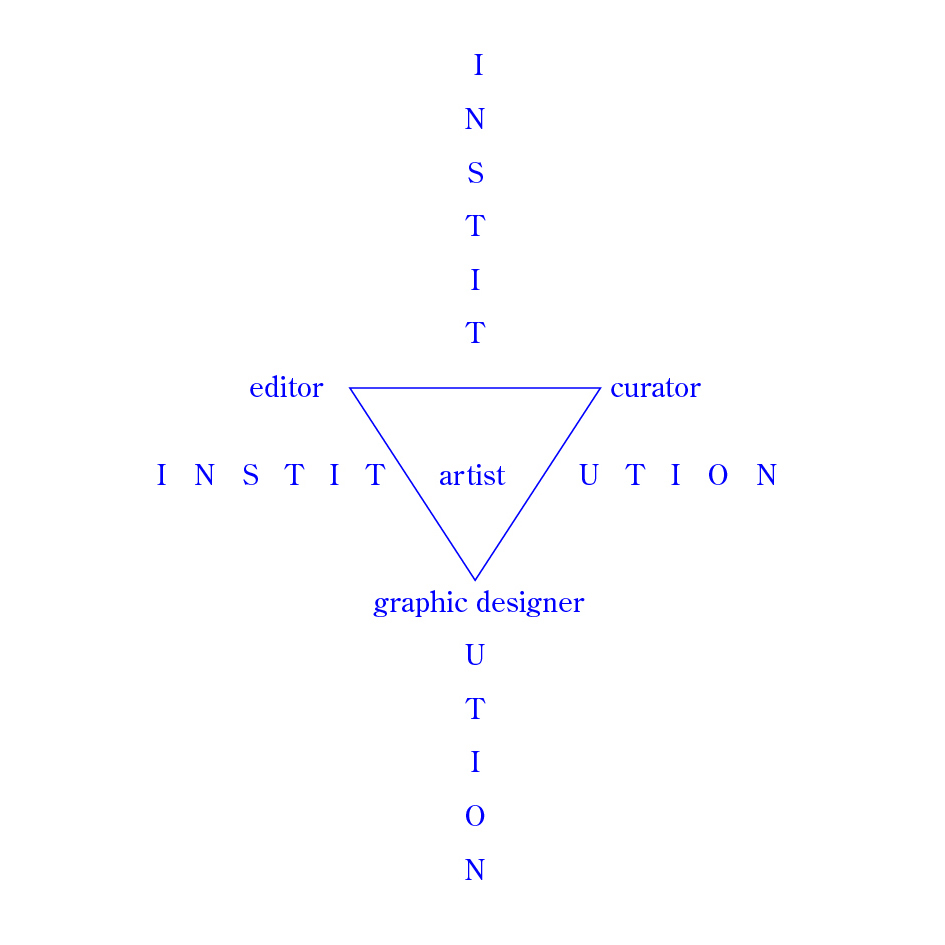

McCarthy, S. (2013) The Designer as Author, Producer, Activist, Entrepreneur, Curator & Collaborator: New Models for Communicating. Amsterdam: Bis Publishers.

McCoy, K. (1990) ‘The New Discourse’, Cranbrook Design: The New Discourse, McCoy, K. and McCoy, M. (eds.). New York: Rizzoli.

Meggs, P. B. and Purvis, A. W. (2011) Meggs’ History of Graphic Design. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Menon, C. & Patteeuw, V. (2018) ‘Magazine Architecture’, Karel Martens and The Architecture of the Journal, OASE, 100. NAi Publishers. [online] Available at: https://www.oasejournal.nl/en/Issues/100 [Accessed 22 March 2025].

Mermoz, G. (1995) ‘On Typographic Reference (Part One)’ Emigre: Mouthpiece 36, n. pag. Sacramento: Emigre.

Miller, N (1988) Subject to Change: Reading Feminist Writing. New York: Columbia University Press.

Muhle, M. (2011) ‘Re-Enacting Art History’, Images or Shadows, 174–188. Dublin: Irish Museum of Modern Art.

Mukařovský, J. (1984) ‘Poetic Reference’, Semiotics of Art: Prague School Contributions. Titunik, I and Matejka, L (eds.). Cambridge: MIT.

Mould, O. (2020) Against Creativity. London and Brooklyn, NY: Verso.

Müller-Brockmann, J. (2007) Grid Systems in Graphic Design: A Visual Communication Manual for Graphic Designers, Typographers and Three Dimensional Designers. Salenstein: Niggli.

Murray, J and Evers, D. (1989), ‘Theory Borrowing and Reflectivity in Interdisciplinary Fields’, Advances in Consumer Research, 16, 647–52. Association for Consumer Research.

Pantenburg, V. (2011) ‘Medium Promiscuity: Notes on Gerard Byrne’s Film and Video Work’, Images or Shadows, 157–166. Dublin: Irish Museum of Modern Art.

Pater, R. (2021) CAPS LOCK: How Capitalism Took Hold of Graphic Design, and How to Escape from It. Amsterdam: Valiz.

Penman, I. (2002) ‘On the Mic: How Amplification Changed the Voice for Good’, Undercurrents. London: Continuum.

People Meet in Architecture: Biennale Architettura Participating Countries/Collateral Events (2010), Venice: Fondazione La Biennale di Venezia and Marsilio.

Potts, A. (1999) ‘The Minimalist Object and the Photographic Image’, Sculpture and Photography: Envisioning the Third Dimension. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Poyner, R. (ed.) (1991) Typography Now: The Next Wave, 53. London: Booth Clibborn Editions/ Internos Books.

Rock, M. (1996) ‘The Designer as Author’ Eye 20. London: Eye Magazine Limited. [online] Available at: https://www.eyemagazine.com/feature/article/the-designer-as-author [Accessed 28 March 2025].

Rock, M (2013) ‘Fuck Content’, Multiple Signatures: On Designers, Authors, Readers and Users. New York: Rizzoli International. [online] Available at: https://2x4.org/ideas/2009/fuck-content/ [Accessed 21 March 2025].

Rose, S. (2017). The Lived Experience of Improvisation: In Music, Learning and Life. Chicago: Intellect Books.

Sanders, J. (2016). Adaptation and Appropriation. London and New York: Routledge.

Scalbert, I. (2013) Never Modern. Zürich: Park Books.

Shaw, P. (1996) ‘The Definitive Dwiggins no. 81 – Who Coined the Term “Graphic Design”?’ [online] Available at: https://www.paulshawletterdesign.com/2018/01/the-definitive-dwiggins-no-81-who-coined-the-term-graphic-design/[Accessed 21 March 2025].

Shaw, P. (2020) ‘The Definitive Dwiggins no. 81A—W.A. Dwiggins and “Graphic Design”: A Brief Rejoinder to Steven Heller and Bruce Kennett’. [online] Available at: https://www.paulshawletterdesign.com/2020/05/the-definitive-dwiggins-no-81a-w-a-dwiggins-and-graphic-design-a-brief-rejoinder-to-steven-heller-and-bruce-kennett/ [Accessed 21 March 2025].

Silberman, M., Giles, S., and Kuhn, T.J. (eds.) (2021) Bertolt Brecht: Brecht on Theatre. London, New York, Oxford, New Delhi, Sydney: Bloomsbury Academic.

Simondon, G. (1980) On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects. University of Western Ontario.

Simondon, G. (2017) On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects. Minneapolis: Univocal Publishing.

Smith, D. (2008) ‘Delayed Departures: Cinema/Venice Architecture’, The Lives of Spaces, 135–145. Campbell, H., Martin-McAuliffe, S., Ward, B., Weadick, N. (eds.). Dublin: Irish Architecture Foundation/ UCD.

Smithson, R. (1996) ‘Art Through the Camera’s Eye’, Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings. Jack Flam (ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Stiegler, B. (1998) Technics and Time, 1: The Fault of Epimetheus. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Tarfuri, M. (1980) Theories and History of Architecture. New York: Harper & Row.

Théberge, P. (1997) Any Sound You Can Imagine: Making Music/Consuming Technology. Hanover & London: Wesleyan University Press.

Thrift, J. (2000) ‘8vo: type and structure’ Eye 37. London: Eye Magazine Limited. [online] Available at: <https://www.eyemagazine.com/feature/article/8vo-type-and-structure> [Accessed 21 March 2025].

Thomson, E. (1993) ‘The Literature of Graphic Design’, Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America, 12 1, 7–11. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Art Libraries Society of North America Stable.

Tracy, A. (2019) ‘The Essay Film’. [online] Available at: https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/features/essay-film [Accessed 28 March 2025].

Triggs, T. (2010) Fanzines: The DIY Revolution. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

van Toorn, J. (2009) ‘Design and Reflexivity’, Graphic Design Theory: Reading from the Field, 102–106. Armstrong, H. (ed.). New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

van Toorn, J. and Crouwel, W. (2015) Excerpts from ‘The Debate: The Legendary Contest of Two Giants of Graphic Design’. Monacelli Press. [online] Available at: https://designobserver.com/feature/the-debate/38883/ and https://designobserver.com/feature/the-debate-part-2/38884 [Accessed 22 March 2025].

VanderLans, R. (ed.) (1990) Emigre: Sound Design, 16 n. pag. California: Emigre Graphics

Walker, S. (2023) ‘Design is… Lost’, The Design Journal: An International Journal for All Aspects of Design 26. [online] Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14606925.2022.2154962 [Accessed 21 March 2025].

Walters, J. (2010) ‘Joost Grootens: Paper planet’, Eye 78, 68–83. London: Eye Magazine Limited.

Wibberley, C. (2012). ‘Getting to Grips with Bricolage: A Personal Account’ The Qualitative Report, 17, Article 50, 1-8. NSU Florida (nova.edu). Available at: http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR17/wibberley.pdf [Accessed 14 November 2020].